Stereotype is defined, in sociology, as “a simplified and standardized conception or image invested with special meaning and held in common by members of a group.” (dictionary.com), and the act of stereotyping is to cast someone in a stereotype (same source). Since a stereotype is a simplified conception, it stands to reason that the sources of stereotypes are often themselves simplified (think of thuggish gangsta rappers or satanic black metal musicians). As a veteran of the US Air Force, I often stereotyped Marines as macho imbeciles who couldn’t think for themselves. The verb form of the word “judge” has many different nuanced meanings (dictionary.com), but the common thread is that judgement is, as an act that conclusive after evidence is brought forth and examined. After meeting some Marines at the DoD Weather School at Chanute AFB, I came to judge Marines, on the whole. as honorable and brave people who chose a different path of service to our country.

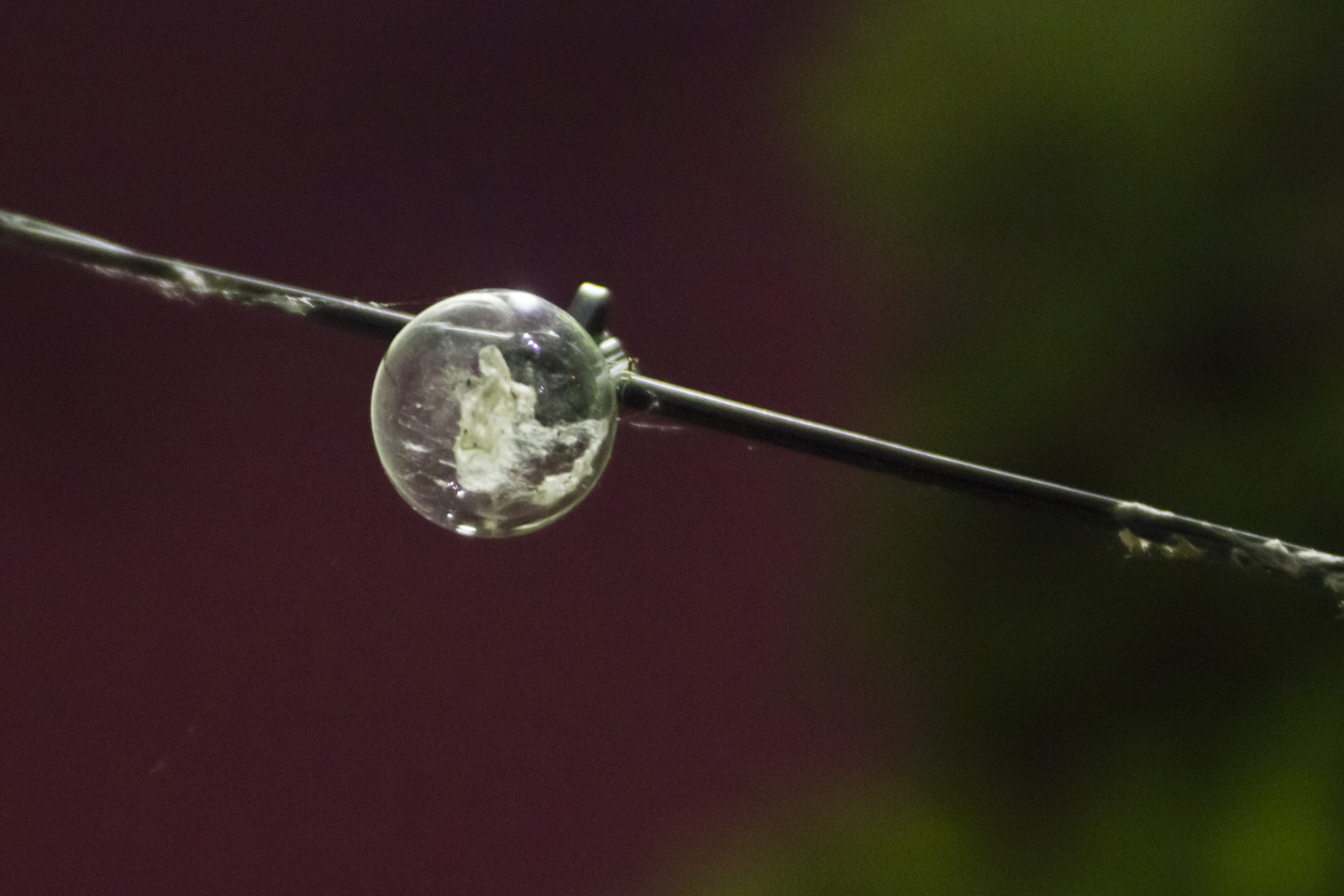

This verbose examination of the two words is important in understanding the series entitled “Judging America” from Joel Pares. Below is one of the images from the series:

As the viewer can see, the image is a diptych of sorts. It is an animated .GIF file. The first image is a portrait set against a black background. In the example above, it is a white man wearing a tank top. He’s holding a noose in one hand and the flag of the Confederacy in the other. After about 10 seconds, the image morphs into a portrait of someone against a tan background with text at the bottom revealing the identity of the person in the portrait. It’s the same person, but now we see him wearing a casual outfit and carrying a Bible. His name is Jack Johnson, and he’s a full time Christian pastor and missionary.

There is no artist statement on the artist’s website, so all I have to go on regarding the concept of this project are words from a Petapixel.com article:

They say not judge a book by its cover, for photographer Joel Parés‘ series “Judging America,” that’s exactly what he wants you to do… at first. Presented as simple portrait GIFs, Parés wants you to start by judging the book — or in this case person — by his or her ethnicity, profession, or sexual orientation, and then, just as you’ve decided what it is you want to believe about the person you’re looking at, he reveals the reality.

There’s the setup of this project. Now let’s first dive in to the formal elements.

The presentation as animated .GIF files is a novel one for diptych images, and one I have never personally come across. Normally, a diptych is one image made up of two separate frames (think of my Armed and … series), but here we have one frame that contains two images that are presented serially. Obviously, this raises some financial challenges as presenting the project in way that has the intended impact would require some rather expensive computer equipment. The least expensive option would probably require a computer and a pico projector for each diptych. The color balance is consistent throughout, even if some of the digital processing is a bit heavy handed. In some of the images, the HDR-style processing was taken a little too far and gives some of the subjects an almost cartoonish look. In terms of composition, there is nothing really special going on in these images. The portraits themselves are rather conventional. I did, however, note that not all of the images were consistent with their use of the frame. As this is a digital project, this could be dismissed, but it could also pose problems later should Pares ever decide to present printed images.

Now that the formal elements are out of the way, it’s time to take a much more critical view of the images. Pares is presenting these diptychs as follows – the first image is that of a portrayed stereotype, while the second is the reality of that particular person. In each image, we are presented with someone from a different ethnic or cultural background, with one case being sexual orientation and yet another being an occupation. Pares wants us to judge the person, then find out how wrong we were in that judgement when the truth is revealed.

It’s all about the context. Pares removes any context external to the subject (namely, an environment) and, using the relative safety of the studio (where images are created from anything that can be imagined), adds his own context to the subject. In all of these images, we see a blatant projection of a stereotype of a particular subject – a Latino gardener, an Asian nail salon employee, a black thug, a Middle Eastern terrorist, et al. All of these negative images are created from, what I can only assume, is Pares’ imagination as there is no artist statement to explain the process by which he arrived at these stereotypes. In stripping the environment and adding his own context, one wonders if these are not a projection of his own stereotypes and prejudices of those from a culture, ethnicity, sexual orientation, or occupation that is not his own. We never get to see just the person, we only get to see what Pares wants us to see.

If one sees a man snarling and wielding 2 guns, a woman holding an AK-47, or a white man with a noose, without any other context, how does one not tend to think negatively, especially given the heavy handed nature with which it is presented, especially through his very effective use of color? Again, there is no artist statement, so there is nothing on which to base an answer to that question.

And that brings up the difference between the words stereotype and judgement. Pares shows us the stereotype (from whose perspective?) and wants us to make a judgement from only the evidence he presents. Perhaps this is only the humanist in me, but I believe a majority of people are capable of realizing that there is not enough evidence presented in the images in order to make a sound judgement.

Finally, the viewer is presented with the truth of that particular person. Pares goes from a menacing black color cast to a warm brown color cast, in order to temper the negative judgement made by the viewer in the previous image. For this author, it had quite the opposite effect. The feeling I am being manipulated is closer to the emotion that these images evoke when I view this project. Res ipsa loquitur.

Why can’t an Asian woman attending a graduate program at Stanford also work in a nail salon? Why would we assume that a man with the word “Queer” tattooed across his chest and wearing a boa couldn’t be an outreach worker? Why would we assume that just because one wears glasses and carries a backpack that he’s a nerd?

Pares was effective with one diptych. Jane Nguyen is an Asian lady dressed as an exotic dancer in the stereotype image while in the truth image we find out that she is a widowed mother of three children. When it comes to seeing occupations, the person’s life outside can never be known unless it’s revealed. The occupation of exotic dancer carries with it a myriad of different negative stereotypes. There also exist many different reasons why one would become an exotic dancer.

If this had been a critique on how entertainment and news media portray those of different cultural and ethnic backgrounds as well as sexual orientations and occupations, then this heavy handed approach could possibly take on a greater validity. Better yet, why can’t we see the subjects in their environments and try to see those elements of the environment that might give rise to a stereotype? In this way, the artist’s hand is minimized, and then the selective nature of photography allows for a more natural narrative to flow, and a lot less manipulation of the viewer on the part of the artist takes place.

In the end, I’m left with the feeling that the thesis was developed, but as the project proceeded, Pares failed to adjust his thesis for the results he was getting. Then, instead of then reexamining the results, the decision was made to push ahead anyway and try to force the art to fit into the parameters of the original thesis (this goes back to my issues with conceptual art). Again, without an articulated artist statement, this is all supposition, but a reasonable person could come to this “judgement.” As artists, sometimes the art teaches us. I’ve personally learned a lot about myself in my last couple of projects, and even had to adjust my thesis for one of them as what I learned contradicted my formal assumptions. This is how we learn and grow as artists.

As to the stereotypes and judgements of US Marines, as a veteran of the USAF, it is all in the spirit of friendly inter-service rivalry. Semper fidelis, Mr. Pares!